News – Sheridan Media

Mountain Man John Colter was one of the leading explorers in the early days of the frontier. He is best known as the first known European to enter the region which is now known as Yellowstone National Park, and to see the majestic Tetons during the winter of 1807-1808. He is also known for his courage, and for ‘Colter’s Run’ where he ran the gauntlet from the Blackfeet Indians and survived. He is also considered to the be first known Mountain Man. This is his story.

The Daily Boomerang, February 27, 1892 – When Hot Springs were First Discovered. America had been discovered, and the colonies were feeling their way toward the Pacific Ocean. In the vanguard was the famous expedition of Lewis and Clarke, which went overland to the mouth of the River Colombia. John Colter was a hunter in this expedition, and by some chance he went across the mountains on the old trail of the Nez Perces Indians which leads across the divide from the Missouri waters to those of the Columbia. When he came back from the Nez Perces trail he told most wonderful tales of what he had seen at the head of the Missouri. There were cataracts of scalding water which shot straight up into the air; there were blue ponds hot enough to boil fish; there were springs that came up snorting and steaming, and which would turn trees into stone; the woods were all of holes from which issued streams of sulfur; there were canyons of untold depth with walls of ashes full of holes which let out steam like a locomotive, and there were springs which looked peaceful enough, but which at times would burst like a bomb.

Everyone laughed at Colter and his yarns, and this place was familiarly known as “Colter’s Hell.” But for once John Colter told the truth, and the truth could not easily be exaggerated. But no one believed him. When others who afterward followed him over the Nez Perces trail told the same stories, people said they had been up to “Colter’s Hell” and had learned to lie.

Later, Jim Bridger also told of the wonders of Yellowstone, but no one believed him either. Of course, Bridger was a born storyteller, and he had no problem embellishing on the truth. One of his tales of Yellowstone was seeing the upright petrified trees, complete with “petrified birds singing petrified songs.” They were known as ‘Bridger’s Lies.’ Even though these early explorers were not believed at the time, if soon became clear they were, (mostly) telling the truth about Yellowstone.

The Sheridan Post, March 26, 1922 – The outstanding man of the Lewis and Clark expedition, after the commanders, was John Colter, an adventurous spirit, concerning whose prowess and achievements many stories were told in the west of the old days. When the famous expedition to explore the un-known northwest was being organized, Colter enlisted under Captains Lewis and Clark as a common soldier, and the heart-breaking trip across the continent by these intrepid explorers of a century ago was to him a great adventure. He was a frontiersman of the Daniel Boone type, and because of his knowledge of woodcraft and his devotion to duty proved invaluable to the leaders of that undertaking. On the return trip, when the expedition reached Fort Mandan, Colter applied to Lewis and Clark for his discharge. The arduous part of the long journey to and from the Pacific was about over, and all that remained to negotiate the last leg of the journey was to float down the Missouri and Mississippi rivers to St. Louis.

Colter’s good record had won for him a high place in the esteem of his superiors, anti although they were surprised at his request, it was granted. This was in 1806. The Upper Missouri river country then abounded in peltry wealth, particularly in beaver, the pelts of which went current for cash in all the western settlements. Colter proposed to remain in this paradise of the trapper, with two frontiersmen who had followed up the expedition, and trap for beaver. And when they turned their backs on Lewis and Clark these three were the only men of the white race in all the northwestern country within the confines of what is now the United States.

Much of the time alone and always on foot, carrying his arms and provisions with him wherever he traveled, Colter explored the Upper Missouri country, always going where no white man had been before him, and in his migrations discovered the Yellowstone wonderland and the Big Horn River; was the first white man to cross the passes at the head of Wind River, or to see the country in which the Colorado River heads, and was first to penetrate the Jackson’s Hole country. When Colter and the two trappers separated from Lewis and Clark they went into the Yellowstone country.

They took many pelts that first winter, and when spring came Colter decided to return to St. Louis. He built for himself a dug-out canoe, fashioned out of a log, loading part of his furs, launched his craft and started on his long journey to civilization. Fur trading in those days was one of the ‘ first sources of wealth, and the stories told by the men of the Lewis and Clark expedition, when they returned to St. Louis, of the opportunities in the fur trade, had excited many, and among others Manuel Lisa, a man of some means, and who was afterwards to become a noted trader. Lisa organized a company and equipped an expedition to penetrate the Upper Missouri country and establish trading posts. This expedition was on its way up the river, when, at the mouth of the Platte, Lisa met Colter. Colter’s fame had reached St. Louis in the meantime, and Lisa knew him for a wood craftsman of ability.

He persuaded Colter to return to the northwest. Colter led Lisa and his keel boats to the mouth of the Big Horn, on the Yellowstone, where on Colter’s advice, Lisa built his first post which he called Fort Manuel. This was the first habitation of a white man to be built west of Fort Mandan.

His post established, Lisa sent Colter out into the Indian country to advise the Indians of that. The white traders were ready to do business, and would trade gun sand goods and trinkets, all dear to the heart of the Indian, for pelts and furs.

With his pack on his back and carrying his gun and ammunition, and perhaps some samples of goods to excite the curiosity of the Indians, Colter fared forth on his walk of a thousand miles through the wilderness, the pioneer commercial traveler of the northwest. Out in the Jackson’s Hole country Colter met a war-party of Crow Indians, man-hunting for the Blackfeet. Colter had been with Captain Clark on the Marias river when he had to kill a Piegan, an ally of the Blackfeet, so Colter, who could not keep out of a fight, cast his lot with the Crows and in the battle that followed the Blackfeet were defeated. They attributed their defeat to the prowess of the white warrior who was fighting with their enemies.

Perhaps this incident, following the tragedy of the Marias, helped to start the 70 years of warfare between the Blackfeet and the whites.

In this fight Colter was wounded in the leg, and although the wound was a severe one he continued his journey in Lisa’s interests, traveling several hundred miles, visiting various tribes, and finally arriving at Fort Manuel. It was on this return journey that he discovered Yellowstone geysers and lake. There are many romantic stories of the exploits of Colter, and perhaps the most interesting one has to do with a thrilling adventure in which he figured with a narrow lethal margin, the scene of which was in the country where the Jefferson and Madison Rivers, joining, form the Missouri.

This country was claimed by the Blackfeet, who were always ready to fight trespassers. Colter and a man named Potts had established a camp there and were trapping beaver. They knew of the hostilities of the Blackfeet, but the beaver was abundant and they remained. One morning the trappers were out on the river in a canoe when several hundred Blackfeet warriors appeared on the bank. A chief beckoned the white-men to come ashore. Colter knew that it was useless to attempt to escape, and had just grounded the canoe when an Indian seized Potts’ gun. Colter wrested the weapon from the Indian and handed it back to Potts. Potts shoved the canoe back into the stream, and as he did so was shot through the groin with an arrow. “I’ll get one of them before I die,” he said as he leveled his gun and shot an Indian dead. The next instant he was shot through and through with a dozen arrows.

The Indians seized Colter, who expected every moment to be his last. They stripped him stark naked, and called a council to determine the manner in which he should be put to death. Finally they decided that he should run for his life. A chief conducted him several hundred yards to the front of the Indians and pointing towards the Madison River, perhaps five miles away, in sign language, told him to run.

Colter, who was speedy on his feet, ran as he had never ran before, and behind him over the flat prairie sped the fastest runners of the Blackfeet nation. Colter’s moccasins had been taken from him, and his feet were bleeding from contact with the cactus. When he had made about half the distance to the river, and the blood was flecking from his mouth in his effort, he thought he could go no further. He turned, and close behind him was a solitary runner, far ahead of the others.

The Indian, who was also nearly exhausted, attempted to hurl his spear, and in doing so fell, the shaft of the weapon breaking under him. Almost instantly Colter had the spear and had driven it through the body of his pursuer. Colter, in telling of this exploit, said the killing of this Indian seemed to give him new life. He continued his dash for the river, now hopeful that he might escape.

Behind him came the enraged Indians, made doubly ferocious by the killing of their best runner. Finally Colter reach the river and looked about him. Close to the bank was a large beaver house. The beaver builds its habitation with the entrance under water. Colter, as a last resort, dived into the deep water, came up under the beaver house, found the entrance and was safe. When his enemies came, he was out of sight, sitting tight in the beaver house, and although the Indians beat about the place for hours, did not discover him.

Late at night he ventured forth, naked and without food, and started on his journey for Lisa’s fort, which he reached, almost dead from exhaustion, 11 days later. He had promised himself that he would never go back into the Three Forks country, but a short time later he joined the Andrew Henry expedition which went to within a mile of the scene of this remarkable adventure, and built a trading post. This was only just completed when the Blackfeet attacked it in force, killed most of the men garrisoning it, and drove the rest away. After this fight in which he narrowly escaped with his life, he returned to St. Louis, married and the northwest knew him no more.

John Colter, explorer and mountain man, was a part of the opening of the west, and he was the first white man to see the wonders of Yellowstone.

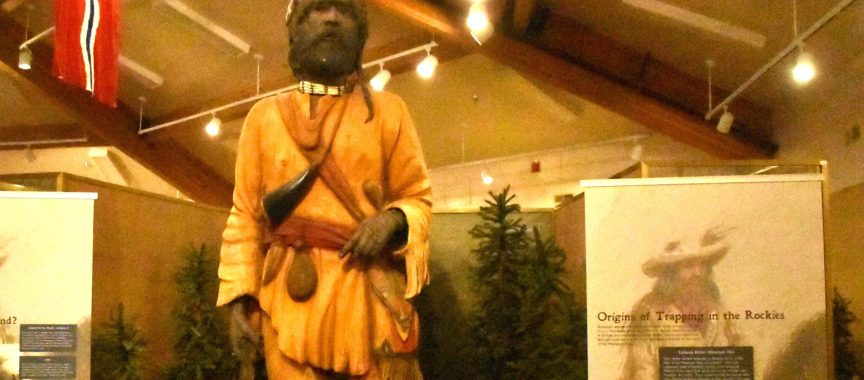

(Except for photos of Yellowstone, displays are in the Museum of the Mountain Man, Pinedale, Wyoming. With thanks.) Vannoy photos

Last modified: August 18, 2025